The Rise of the Gupta Power

The Scythian conquerors of India had received their first great check

Chandra Gupta I

Samudra Gupta

Samudra Gupta, the next king, is probably the greatest of his house. The exact limits of his reign are not known. He probably came to the throne sometime after AD 320 and died before AD 380, the earliest known date of his successor. He is not altogether unknown to tradition. He appears to be mentioned in the Arya-manju-sri-mula kalpa, and also in the Tantrikamandaka, a Javanese text. A Chinese writer, Wang-hiuen-tse, refers to an embassy sent to him by Sri Meghavarma (-Vanna), king of Ceylon, to seek permission to build at Bodh-Gaya a monastery for Ceylonese pilgrims. But the most detailed and authentic record of his reign is preserved in a contemporary document, viz. the Allahabad Pillar Inscription, a eulogy of the emperor composed by Harishena.

The eulogy of Harishena is damaged in several parts so that it is difficult to follow the sequence of events. The Gupta monarch seems at first to have made an onslaught on the neighbouring realms of Ahichchhatra (Rohilkhand) and Padmavati (in Central India) then ruled by Achyuta and Nagasena. ‘He captured a prince of the Kota family and then rested on his laurels for a period in the city named Pushpa, i.e. Pataliputra. Whether the Kota dynasty actually ruled in Pushpapura or Pataliputra about this time, and were dispossessed of it by the Gupta conqueror, is not made clear in the damaged epigraph that has come down to us. Other indications point to Sravasti or a territory still farther to the north as the realm where the Kota-kula ruled. A subsequent passage of the inscription names along with Achyuta and Nagasena several other princes of Aryavarta or the upper Ganges valley and some adjoining tracts, who were violently exterminated. These include Rudradeva, Matila, Nagadatta, Chandravarman, Ganapati Naga, Nandin and Balavarman. The identity of most of the princes named in this list is still uncertain. Matila has been connected by some scholars with the Bulandshahr district in the centre of the Ganges-Jumna Doab, while Ganapati Naga seems to be associated by numismatic evidence with Narwar and Besnagar in Central India. Chandravarman is a more elusive but interesting figure. Suggestions have been made that he is identical with a ruler of the same name, the son ofSamudragupta gold coin Simhavarman, mentioned as the lord of Pushkarana in an inscription discovered at Susunia in the Bankura district of West Bengal. His name has also been traced in the famous Chandravarmankot in the Kotwalipada pargana of the Faridpur district of Eastern Bengal.

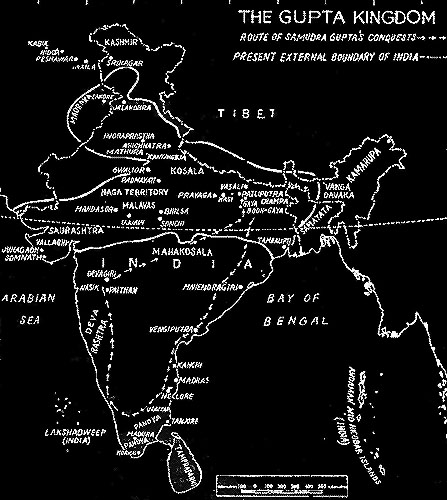

The great Gupta conqueror is next represented as reducing to the status of servants the forest kings apparently of the Vindhyan region. In an earlier passage we have reference to a grand expedition to the south in the course of which the emperor captured and again set at liberty all the kings of the Deccan. The rulers specially named in this connection are Mahendra of Kosala in the Upper Mahanadi valley, Vyaghra-raja or the Tiger king of the great wilderness named Mahakantara, Mantaraja of Kurala, Mahendragiri of Pishtapura or Pithapuram in the Godavari district, Svamidatta of Kottura somewhere in the northern part of the Madras Presidency, Damana of Erandapalla possibly in the same region, Vishnugopa, the Pallava king of Kanchi in the Chingleput district, Nilaraja of Avamukta, Hastivarman, the Salankayana king of Vengi lying between the Godavari and the Krishna, Ugrasena of Palakka, probably in the Nellore district, Kubera of Devarashtra in the Vizagapatam district and Dhananjaya of Kusthalapur, possibly in North Arcot.

The reference to the liberation of the southern potentates shows that no attempt was made to incorporate the kingdoms of the Deccan south of the Nerbudda and the Mahanadi into the Gupta empire. From the territorial point of view the result of the brilliant campaigns of Samudra Gupta was the addition to the Gupta dominions described in the Puranas, of Rohilkhand, the Ganges-Jumna Doab, part of Eastern Malwa, perhaps some adjoining tracts and several districts of Bengal. The annexation of part of Eastern Malwa is confirmed by the Eran inscription. The suzerainty of the great Gupta, as distinguished from his direct rule, extended over a much wider area, and his imperious command was obeyed by princes and peoples far beyond the frontiers of the provinces directly administered by his own officers. Among his vassals we find mention of the kings of Samatata (in Eastern Bengal), Davaka (probably near Nowgong in Assam), Kamarupa (in Western Assam), Nepal, Kartripura (Garhwal and Jalandhar) and several tribal states of the eastern and central Punjab, Malwa and Western India, notably the Malavas, Yaudhevas, Madrakas, Abhiras and Sanakanikas. The descendants of the Kushan ” Son of Heaven”, many chieftains of the Sakas, the Ceylonese and several other insular peoples hastened to propitiate the great Gupta by the offer of homage and tribute or presents. It was presumably after his military triumphs that the emperor completed the famous rite of the horse-sacrifice.

Great as were the military laurels won by Samudra Gupta, his personal accomplishments were no less remarkable. His court poet extols his magnanimity towards the fallen, his polished intellect, his knowledge of the scriptures, his poetic skill and his proficiency in music. The last trait of the emperor’s character is well illustrated by the lyricist type of his coins. He gathered round himself a galaxy of poets and scholars, not the least eminent among whom was the warrior-poet Harishena who resembled his master in his versatility. Both Samudra Gupta and Asoka set before their minds the ideal of world-conquest by means of parakrama. Parakrama, in the case of the Maurya, was not warlike activity but vigorous and effective action to propagate the old Indian morality as well as the special teaching of the Buddha. In the case of the Guptas it was an intense military and intellectual activity intended to bring about the political unification of Aryavarta, the discomfiture of the foreign tormentors of the holy land and an efflorescence of the old Indian culture in all its varied aspects – religious, poetic, artistic.